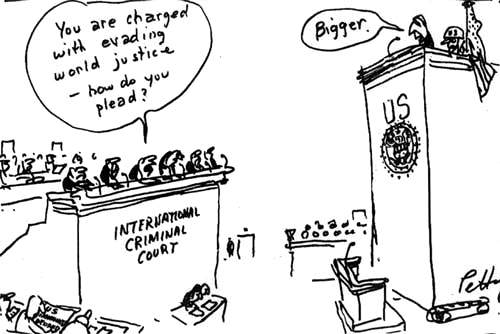

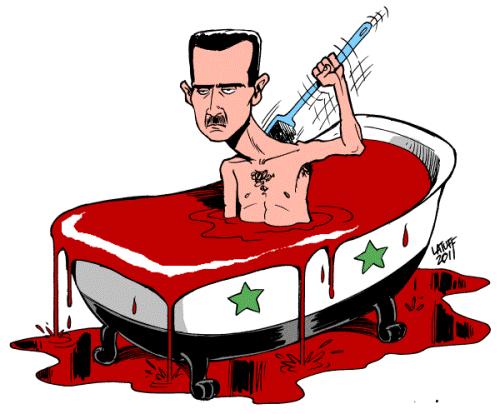

Hilary Clinton recently suggested that Syrian President, Bashar Assad, fit the definition of a war criminal. Could the US be inching towards endorsing another UN Security Council referral to the International Criminal Court? Not so fast. Clinton added that, despite the likelihood that Assad was guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity, any attempt to bring him before the ICC would “complicate a resolution of a difficult, complex situation because it limits options to persuade leaders perhaps to step down from power.” Clearly, the peace-versus-justice debate is alive and well.

Hilary Clinton recently suggested that Syrian President, Bashar Assad, fit the definition of a war criminal. Could the US be inching towards endorsing another UN Security Council referral to the International Criminal Court? Not so fast. Clinton added that, despite the likelihood that Assad was guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity, any attempt to bring him before the ICC would “complicate a resolution of a difficult, complex situation because it limits options to persuade leaders perhaps to step down from power.” Clearly, the peace-versus-justice debate is alive and well.

A familiar pattern is emerging in Syria. The continuing humanitarian crisis and the lack of a coherent response from the ‘international community’ in Syria has inevitably left many to ponder what possible actions could now be appropriate. Once again, observers are seemingly divided between two camps: one, tired of a lack of action and driven by examples where inaction has led to devastating tolls on human life and which screams “act first, think later”. The other, more calibrated and wary of past experiences in Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere urging international actors to “think first, act later.”

There appears to be no coherent response on the horizon to address the acts of atrocity in Syria. While some response is desperately needed, this lull does provide an opportunity for sober reflection on the ever-evolving tools to effectively address and end atrocities.

This essay is based on research I am currently conducting and offers an attempt to grapple with the relationship between the ICC and the UN Security Council. As such, it delves into the ever-shifting sands at the nexus of international politics and international criminal justice in the wake of the Libyan intervention.

Negotiating the ICC’s Independence

The contemporary emergence of international criminal justice and the creation of the ICC can be seen within the context of a particular political ethos, namely liberal cosmopolitanism. Liberal cosmopolitanism seeks to displace the state – or any collective for that matter – as the primary moral and political unit in international relations. It is the individual human’s experience, security and rights that must be, above all, privileged. The end of the Cold War, characterized as it was by realpolitik and stagnation on many human rights questions, provided the elbow room necessary for liberal cosmopolitan projects – previously deemed idealistic or utopian – to institutionalize. Whatever necessary impetus was missing, guilt stemming from the inaction by the international community in the face of the Rwandan Genocide and the Srebrenica massacre fueled the liberal cosmopolitan cause.

Out of this unique historical and political moment emerged a set of concepts, practices and institutions which, students of international politics often argue, constitute the very contours of international politics: international criminal justice; human security; the responsibility to protect; and liberal peacebuilding. All, at their very core, share the view that it is the individual, above all else, who must be ‘protected’ and, when at risk, ‘saved’.

Given this context, it should be unsurprising that, during the Rome Statute negotiations, a key issue of contention was the relationship between the Court and the UN Security Council. Proponents of the ICC sought to guarantee a Court independent of international power politics, one which could transcend the orthodoxy of international relations wherein asymmetries of powers determine whose sovereignty is respected and whose is permeable. ICC advocates were deeply uncomfortable with, suspicious of, and perhaps even feared giving the UN Security Council too much influence over the functioning of the Court. The concern was that if the ICC worked at the behest of the Security Council, it would result in a Court that was an extension of state powers rather than ‘humanity’.

Cozying up to the Security Council

To a remarkable extent, fear of the Court being shaped and determined by the Security Council has dissipated.

If there was any discomfort with the ICC’s first UN Security Council referral – that of Darfur in 2005 – little to no concern was voiced when, in February 2011, Libya became the Court’s second Security Council referral. On the contrary, the Security Council’s action was welcomed by human rights groups without reservation. Richard Dicker, head of Human Rights Watch, heaped praise on the Security Council arguing that it had finally demonstrated that “[t]he United Nations is showing concerted international resolve to pressure Gaddafi and his henchmen to end their murderous attacks on the Libyan population.” Other groups suggested it was a “victory”, “milestone” and “triumph” for international justice.

The Office of the Prosecutor at the ICC was likewise eager and enthusiastic about the Security Council’s referrals. This is most powerfully evidenced by the unprecedented speed with which the Libya referral was accepted and translated into arrest warrants for the Libyan leader, Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, his son and former heir-apparent Saif al-Islam Gaddafi and Libya’s internal and external head of intelligence Abdullah al-Senussi.

For some, like legal scholar, Frédéric Mégret, this proximity is the result of an evolution in the relationship between the ICC and the UN Security Council. In a masterful piece on the subject, Mégret illustrates how “the irresistible attraction of power” leads the ICC to “gravitate towards the Security Council”:

The ICC has had “a tendency to gravitate towards the very power that [it is] supposed to constrain” and finds itself “obsessed with the need to enlist power for [its] cause not only in the sense of needing immediate patrons for the purposes of having certain ideas endorsed, but because [the ICC] depend on power to be implemented in the long term. The irony…,then, is a tremendous tendency to reinforce that which [the ICC claims] to transcend, sovereign states on the one hand, and the Security Council on the other…[T]he ICC’s aspiration to international criminal justice…[is] exposed as ultimately weak and dependent on the very sort of power whose limitations [it] condemn[s]….The Court thus ends up being highly subservient to the Security Council power logic that was supposed to be so lethal to the fundamental justice of international criminal justice…”

It can easily be claimed that this irresistible attraction led the Court to accept Security Council Resolution 1970, a referral which is as much a matter of politics as law or justice.

Political Tailoring: Resolution 1970

The Security Council’s referral politicized the mandate of the ICC in three distinct manners.

First, like the Darfur referral, Resolution 1970 excludes non-ICC states parties. Not only is this of questionable legality, given that it makes a mockery of the principle of equality before the law; this political tailoring of the referral to exclude non-states parties from the ICC’s jurisdiction both undermines the Court’s ultimate aim to achieve universal justice and suggests a hierarchy wherein similar crimes within the same context cannot be similarly investigated and prosecuted. Incredibly, only Brazil raised the exclusion of non-states parties as an issue in the wake of Resolution 1970.

Second, the referral includes a reference to Article 16 of the Rome Statute which allows the UN Security Council to suspend an investigation or prosecution by the Court for 12 months, renewable yearly. Many scholars had believed – perhaps hoped – that Article 16 would be irrelevant in the practice of the ICC. However, its inclusion in the referral, despite the fact that it was not subsequently invoked, has created concerns that the international community may seek to use Article 16 to play fast-and-loose with international criminal justice.

Third, under the referral, the ICC’s temporal jurisdiction in Libya was restricted to events which occurred after February 15, 2011. This restriction on the Court flies in the face of the Rome Statute itself, which stipulates that the ICC can investigate any alleged crimes under its jurisdiction back to July 1, 2002. The restriction means, above all, that the cozy economic, political and intelligence relationships between Western states and the Gaddafi regime may never come to light during an investigation.

Given the above, it is quite simply impossible to say that the mandate given to, and accepted by, the ICC under Resolution 1970 wasn’t political. While the referral and its acceptance ensure that alleged crimes in Libya will be investigated, it guarantees that this will be done selectively – at the behest of the UN Security Council.

A Fatal Attraction?

As I have argued elsewhere, the ICC was left hanging by the UN Security Council and NATO powers. By the summer of 2011, when all avenues to get Gaddafi out of the country had been apparently exhausted, support for the ICC’s work plummeted. By this point, NATO had made the decision to break the military stalemate in Libya and to target Gaddafi himself. In this context, the ICC’s ability to isolate Gaddafi was no longer useful for the NATO powers. The legitimacy offered by associating, if not conflating, the military intervention with the “justice” and “just ends” of the ICC was by this point well-engrained in the popular imagination and narratives of the conflict.

Of course, none of the above prevented a myriad of simplistic and unsupported accounts which suggested that the ICC, above all, stood in the way of a peaceful resolution in Libya. Once again, however, this highlighted the confusion regarding the allocation of responsibility for peace in contexts where the ICC’s mandate is put in motion by the Security Council. Observers typically neglected to ascribe responsibility for the ICC’s involvement in Libya to the Security Council, preferring to allocate blame for alleged negative effects to ICC itself.

Thus, not only was the ICC’s institutional independence bastardized by the Security Council’s tailoring and instrumentalization of the Court’s mandate – but the ICC was subsequently left out to dry.

Unfortunately, it seems the ICC’s Office of the Prosecutor has been only too willing to tether its work to the UN Security Council, offering the Council’s major powers legitimacy in their interventions while leaving the Court, in key regards, at the whim of the Council’s real-politikal calculus. Nevertheless, while it is unclear how widespread the sentiment is, there are some (very healthy) signs of dissatisfaction coming from inside the ICC itself. Christian Wenaweser, who served as the President of the Assembly of States Parties from 2008-2011, recently communicated his concerns:

“Why didn’t the Security Council welcome the arrest of Seif Gaddafy and call on Libya to cooperate with the Court…There is little diplomatic political support from the Security Council on referrals and it is not likely to come… In the future we have to think about the benefits for the Court” of Security Council referrals.”

Between a Rock and a Hard Place

Between a Rock and a Hard Place

The Court is in a rather prickly position, one where there are no obvious good paths. The relationship between the Security Council and the ICC is wrapped in a paradox. On the one hand, a closer relationship between the power-politics of the UN Security Council and the ICC diminishes the quality, legitimacy and, above all, independence of the justice on offer from the Court. On the other hand, without cooperation between the UN Security Council and the ICC, some of the worst international crimes would never be investigated.

Further, the ICC may believe that it needs the international community of states to take its work seriously. Getting the Council to play game – even if it is a high-risk and high-cost game – may be the price to pay to get recognition in the ‘big leagues’.

There may be no good answers, but out of this analysis, the pertinent question becomes: to what extent is the Court and its personnel concerned with this dilemma and how will it be managed?

Regaining Independence

It is worthwhile considering what role the current Prosecutor, Luis Moreno-Ocampo, himself has played in tethering the Court to the Security Council. Moreno-Ocampo has often prioritized gaining the ICC’s work international attention and he has strategically delineated a division of labour wherein he sees a partnership between the Security Council’s responsibility for peace and the ICC’s responsibility for justice.

In this context, the ICC’s next top prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda, has a lot of work to do to regain the real and perceived independence for the Court. If not, the allegations of the Court as being selective and biased against weak states and of the ICC as being in the back pocket of the most powerful states will not only be exacerbated but proven true.

Importantly, there are clear ways in which to regain independence. The Court’s independence could be demonstrated by thoroughly investigating NATO’s role in Libya. The ICC could also be more transparent and forthright about its concerns with Security Council referrals rather than appear overly enthusiastic that the ‘big powers’ are taking it seriously. On the more radical end of the spectrum, the Court could challenge the restrictions placed on its mandate in Libya and extend its jurisdiction to 2002.

Of course, there are obvious doubts that the ICC will be asked by the UN Security Council to intervene in Syria or anywhere else, at least anytime soon. If it is asked, however, the Court should think long and hard whether or not to accept the invitation. The Court and the delivery of international criminal justice may be better off if the ICC politely declined.

———————————————————-

See also my academic piece which deals with this subject here.

This is a bit of an old conversation to bring up, but there remains something strange to me about your painting of the ICC as tempted and compromised by the power of the UNSC. You’re absolutely right that the ICC is playing a political game in which they try to get involved in big cases, which means the run the risk of being instrumentalised by powerful states. Where we part ways, I think, is in understanding why this dynamic emerges. The ICC needs the coercive political power of the UNSC in order to function, whether we focus on a state-centric or cosmopolitan account of the court’s purpose as an institution it needs to either work more closely within the international system or find ways to garner enough power to effect a more fundamental transformation. There’s no law or accountability without political power, so the ICC like any other institution pursues what it needs to survive. Two things strike me about the ICC’s politics (and Ocampo’s in particular): (i) how politically tone-deaf and inept the institution has been, though perhaps its not surprising given the lack of clear purpose for the court beyond fulsome rhetoric; and (ii) the seeming ignorance with which their declamations against having a politics play into the hands major powers. Because the court stands for nothing, against evil but not for anything, there’s no surprise that those actors with concrete ends and the power to effect them will attempt and often succeed in manipulating the court.

Pingback: Libya: a year in the life of an ICC referral « Chris Tenove

I’m not sure I understand your point about extending the ICC’s jurisdiction over Libya. Are you arguing that crimes against humanity (I assume you do not mean war crimes or genocide) were committed between 2002-2011? By whom and when (allegedly, of course)? That’s the first time I’ve ever heard this claim.

I believe Mark is referring to allegations of systematic torture during Gaddafi’s rule in Libya, brought forward e.g. by Human Rights Watch in a 2008 report (http://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/libya_rights_risk_090808.pdf).

If it is systematic, torture can amount to crimes against humanity under the Rome Statute. If not restricted to the time after February 2011 the ICC could have shed light on the involvement of Western powers in that torture as some countries handed over terrorism suspects to Libya to obtain information through torture used as an interrogation technique in Libya.

Thanks for the link, Patrick. It’s an interesting advocacy brief, no doubt. But it doesn’t speak to the issue of crimes against humanity per se, although I do take your point about it being *hypothetically* possible. I realize it’s possible to construct a hypothetical case, but I was wondering if anyone (ICC sources, CICC?) has argued more recently that the cut-off date should be extended retroactively to before the SC referral, and to what end. I haven’t seen (which doesn’t mean it hasn’t been articulated — that’s my question) any serious claim as to potential crimes against humanity, and while the torture example is interesting, I agree, we both know how controversial the whole issue of torture is. More importantly, it is a much harder case to make at trial. I can’t see the Prosecutor wading into those waters, notwithstanding the aspirational but completely non-legal second argument articulated by Mark in his response below.

@Joe – Interesting and thoughtful comment as always. I’m not sure whether I agree with the point that “the ICC needs the coercive political power of the UNSC in order to function”. I agree that it needs cooperation from states to enforce arrest warrants but I’m not convinced that it requires that power from the Security Council itself. But regardless, even if it does, it is really the extent to which the ICC tethers its politics to the Security Council – from necessity or not – that seems problematic. In accepting questionably legal and very problematic referrals without complaint or challenge it sides with a particular type of politics, namely the power-politics / realpolitik of the Security Council. I think that has the potential to risk both the long-term legitimacy of the ICC as well as the delivery of justice.

@Maya – I am referring to two things. First, I am referring to the allegations that Patrick notes in his comment (see also here: https://justiceinconflict.org/2011/09/06/a-remarkable-relationship-us-and-uk-complicit-in-gaddafi-regime-crimes/). Note that the Gibson Inquiry in the UK, for example, has added British complicity in torture allegations to its investigation. Second, I am referring also to the general political relationship between many Western states and the Gaddafi regime that would be exposed in a trial. I have no doubt that, at a trial where the jurisdiction extended to 2002, the defense would seek to shed light on that very cozy relationship. The defense might also seek to get some former leaders, like Tony Blair, to testify as to the relationship between these countries and the Gaddafi regime. Trials expose much more than what crimes were committed and by whom. They contextualize and bring forth evidence on an entire range of subjects that either the defense or prosecution deems of importance.

Pingback: The ICC and Regime Change: Some Thoughts but Mostly Questions | Justice in Conflict

Pingback: Africa and the ICC | Maison de Liberté

Reblogged this on Nilzeitung.

Pingback: Understanding the Syrian Crisis and the International Issues Involved – Society for International Law